The leading lights in contemporary architectural design presented their models and discussed them in the context of Istanbul’s struggle for recognition as a cosmopolitan city. Outstanding engineering achievements, sustainable planning and cultural heritage formed part of a well-orchestrated protocol of declarations of intent to participate in the exclusive set of global cities. The allegorical motto of the congress as well as its point of reference – the legendary oriental bazaar that leaves no desires unfulfilled – transfigure the socio-spatial challenge posed by a rapidly expanding megacity and its hope that it will be saved by quick responses from architects and urban planners (1).

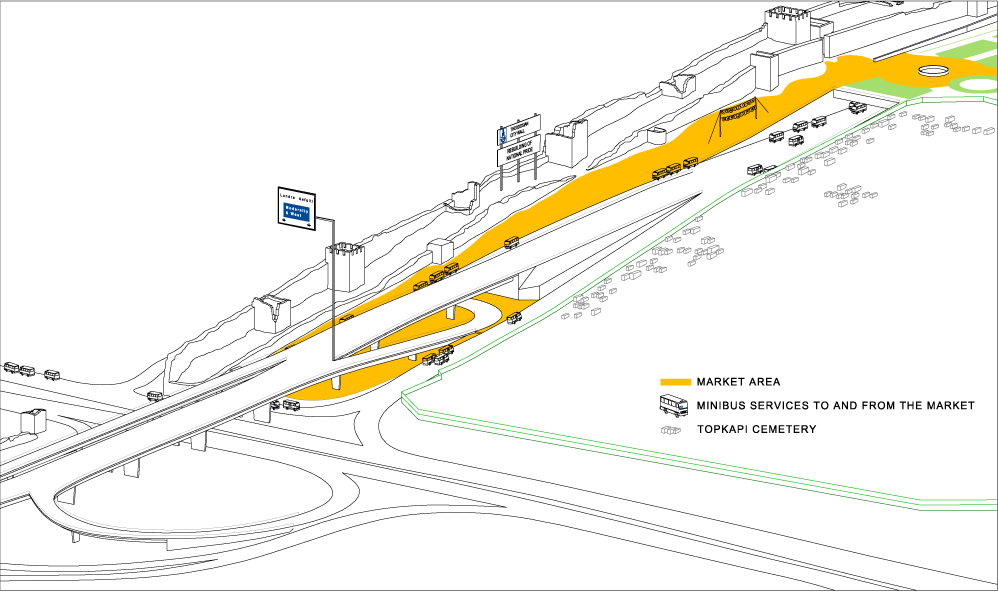

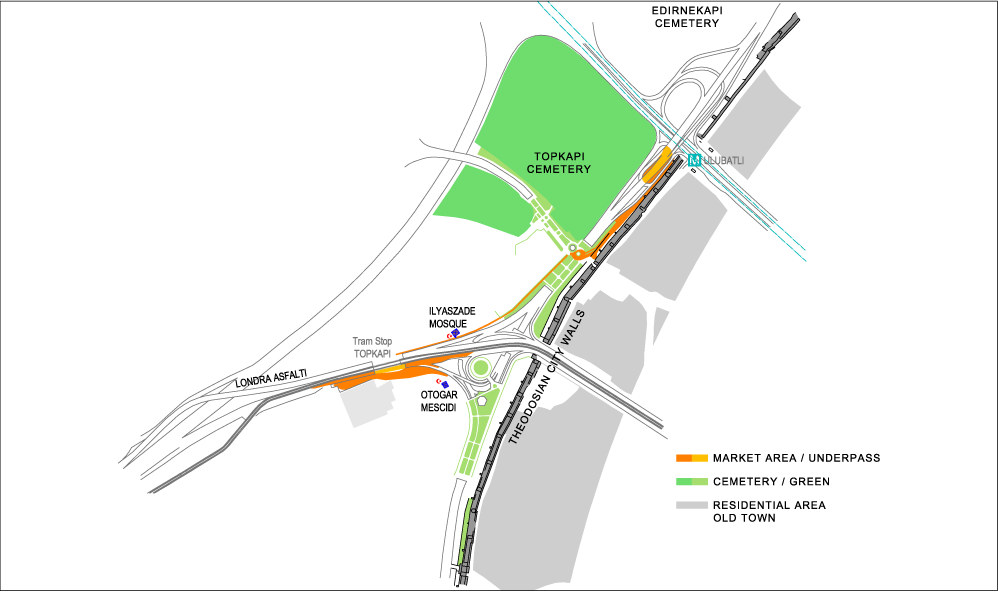

Outside the tourist centres and escaping international attention lies a very different type of bazaar. It is composed of a vast network of provisional, informal street markets that establish themselves right alongside building sites where urban renewal plans are being realised, beneath terraces of city motorways and next to newly constructed tramway lines. These markets disappear as quickly as they materialise, only to reappear elsewhere. This bazaar is not so much a location for trading goods as a space under negotiation. It is a threatening and threatened space which winds its way through the city from site to site and temporarily uses (as the intermediary user of the newly planned infrastructure) the wastelands along the development axes of the planned city.

One of these arose in 2005 before the gates of the Byzantine city wall in the district of Topkapı, where the building sites of two of the main enterprises that took on the job of tidying up the city in the 1980s converge. On the one hand, a traffic network of urban motorways has been created there in the style of modernist US urbanism. On the other hand, the 1,500-year-old Byzantine city fortifications have been reinstated there in their original condition. In nationalist literature, their continual decline and the living conditions in the wretched areas bordering the fortifications had come to symbolise both the impoverishment of Istanbul and the stronghold of true Turkish values (2). Between newly delivered and unused building materials, impassable heaps of crushed stone, and 8-lane motorways, a swarm-like mass fills a black market covering several kilometres. Piles of second-hand goods and fabrics are mixed up on bare ground with new TV sets, refrigerators, pieces of furniture and computers. On days when visitors turn out in strength, several thousand people can be seen negotiating this construction site of the new Istanbul.

read more...

read more...

read more...

read more...

read more...

read more...

read more...

read more...

read more...

read more...

read more...

read more...

read more...

read more...